I was really inspired by the Massumi reading and today’s discussion, so I just wanted to lay out and try to work through some of the additional questions and concerns that occurred to me during today’s class.

First, I’d like to quickly comment on what I read as Massumi’s belief in the idea that living life more intensely makes you freer (214): I agree with this in the sense that by experiencing a situation more profoundly and with more awareness (not necessarily processed by thought, which is an issue I’m going to raise later), one becomes both more deeply embedded into one’s environment (thereby by some definitions more “unfree”) but also freed from the immediate, narrow demands of and possibilities given by articulated ideologies (that is, when there is no ideology on-hand to narrow down and thereby distort the affect of the given situation). I really appreciated the way in which Massumi spoke about freedom as in fact a recognition of constraints, because from conversations I’ve had with certain people (*cough* libertarian anarchists), it seems to me that there is a (perhaps growing) strain of philosophy that advocates a complete overcoming of interpersonal relationships and obligations to other people in pursuit of an almost socially immaculate and therefore “free” individual. (I’m also not sure if this is implied in Nietzschean philosophy? From the little that I’ve read, it didn’t feel that way, but if somebody well-versed in his works could respond, I’d be all ears!) I’m actually also not sure what a development of affect would mean in terms of coming to a sense of social obligations – does more deeply feeling a situation necessitate deeper, more empathetic bonds with other human beings? What obligations arise from that? If living more intensely and thereby more freely means also a deeper involvement in relations between people (bodies, of course, included), what does that say about the social nature of freedom? Basically, how would affect link freedom back to people and obligations to them? Is it that a rejection of the responsibilities of social relationships is only another way of actually limiting affect by resembling a sort of ideology in itself? (Actually, thinking about this has made me also realize how Massumi’s ideas on affect tie back to our other reading on acceptance and change by Earl Vickers – affect can, I think, be experienced as simultaneously both an acceptance of the here and now and also an unlocking of immediate action and change.)

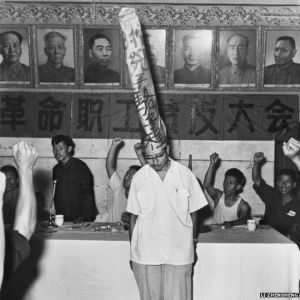

[A semi-related note on ethics: He seems to speak of ethics as a sort of framework/guide to unlocking and directing the affect of a given situation: “Basically the ‘good’ is affectively defined as what brings maximum potential and connection to the situation. It is defined in terms of becoming” (218), and I find his emphasis on a balance between bringing out “maximum potential” and deeper “connection to the situation” important, since the former unleashes while the latter grounds, and an imbalance could result in such dangerous outbreaks of affect (in this situation, I guess they would be irruptions into emotion and actual violence?) as in the Cultural Revolution and other authoritarian/fascist movements. How exactly, concretely, would we relate ethics back to interpersonal relationships and action (from the very abstract notions of recognizing maximum potential and connections to situations)?]

Another question I have that I feel our conversation today partially answered but then raised more questions on (as most good conversations do) is the relationship between what we seemed to describe as a more unconscious affect and a more “conscious” freedom based on deliberate choices. Although Massumi stated that affect involved both mind and body (a dynamism, rather than division, between the two) and thus overcomes “the old Cartesian duality” (215), in the end I feel like it at least doesn’t overcome a gulf between un/sub-conscious and conscious. He specifically says that the sensation, which is a more aware registering of affect, “is not yet a thought” (217) – so it would seem then that affect is even further away from thought than sensation, and even more from emotion. My question, then, is: is it desirable(?)/good(in the ethical sense?) to try to bring affect more to the level of consciousness, so one can more clearly see all the sources of one’s sensations and the possibilities to take? Because if a person is wrapped in and buffeted by the tides of affect, that vulnerability and involvement can easily be manipulated to specific (usually political, I feel) ends. Then, would that consciousness necessitate thought? I, for one, cannot really imagine how it could go without it. Certainly, affect cannot be entirely translated into thought or language or really any medium, I think, but is that something we should strive for nonetheless?

Another point: We briefly commented in class on how literature can describe and explore the affect of the relevant(?) situation or state without ever capturing it in its entirety, which spurred me to think more about literature and other art forms as re-embodying/re-embedding ideas and emotions (which are often abstracted from specific contexts), and raising to awareness by highlight specific aspects of their affect. How do Massumi’s ideas of capture – both the way emotions like anger capture affect and the way art forms capture it – relate to each other?

And a final appeal/question(?): Towards the end of the interview, Massumi seemed to be saying that we now live in an age and space increasingly defined by affect, and the Left’s failure to appeal to and expand affect is a key factor in its failure to gain more popular support. The next course of action, then, seems to be utilizing affect to turn, or at least even out, the tides somehow: as he expressed it, to “meet affective modulation with affective modulation” (234). But such an approach feels oddly like “capitalizing” on affect in the same way such faces of popular affect as Trump have – so is affective appeal really the best way to try to influence political belief and action? How do you make that not manipulative and limiting but still connect it to some sort of concrete political platform? And how do you do that also without falling back on the moralizing logical arguments that he thinks the Left relies on? (Although, to be honest, I do not feel like the Left has been as slow on the affective uptake as he believes.) Basically, I’m re-posing the question he also leaves unanswered: what exactly would “an aesthetic politics” that aims “to expand the range of affective potential” (235) look like and entail?

And some more, very rough ideas I’d like to continue thinking about but don’t have time to write out right now:

The relationship between affective modulation and embedded game design (as in persuasive games)

The relationship between identity politics and aesthetic/affective (though I don’t feel like the two terms can really be used interchangeably?) politics, and how at times (often, I feel, at the same time) you can have use for the solidifying but potentially divisive effect of the former and at others the more open-ended but less concrete(?) quality of the latter (related to how we were saying that emotions like anger can also be necessary to a given situation, if we can still acknowledge its broader affect)

Dread as a very neat example of affect

How some words seem (I’m sure it’s different for each person/community) to produce an immediate affect: Blitzkrieg, for example. Affect is completely context-dependent and relational: Susan Sontag also addressed this, I think, when she wrote that “No ‘we’ should be taken for granted when the subject is looking at other people’s pain” (On Regarding the Pain of Others, 7). Affect differs from population to population, and is in the case she’s examining, is closely tied with politics (for better or worse).

The relation between affect and spectacle – a spectacle may very well produce affect more immediately, but does it last as long as affect created through other means? Is it as profound? I’m thinking about the spectacle of mass rituals, tv recordings, etc., as opposed to the more – is atmospheric or subtle the right word? – affect I experienced in Dread or Gone Home, for example.

This may come completely out of left-field, but the relationship between intense affect and “the zone” that so many artists and sportspeople describe

How does affect relate to memory and remembrance (which I think are distinct – the former more thought-based, the latter also bodily): If affect is less conscious and also more context-dependent and therefore perpetually shifting (compared to, say, beliefs or emotions), would it not therefore be harder to keep in mind through time the motivations towards specific action provoked by a given affect?

The gulf between emotion and affect, which, though bodily, isn’t as often physically expressed (although physically felt), especially as seen in their separation across screens when people are texting, watching videos, etc. Is this a “good” thing? It feels reminiscent of the mind/body split, but it obviously isn’t that. I personally am always fond of the moments when people explode into visible emotion after a period of seemingly imperturbable detachment from the screens their fingers (but not facial muscles, or seemingly any other muscles for that matter) are vigorously interacting with….

The distinctions between emotion, sensation, and affect

The seeming preference for words to channel affect: For example, although advertisements often immediately produce some sort of desire or at least mood in the viewer (harder to say so nowadays though, since we’ve become so inured to ads that – can we call this phenomenon a numbing of affect by its omnipresence, commercialization, and mass distribution?), they often always still rely on words to deliver the punchline of their message. The power of war photographs and other political photographs was also often channeled and narrowed by captions (for example, the following photo, although now seen as evidence of the unfair horrors suffered by intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution, could easily have been described and seen as proof of the righteous vengeance against “counterrevolutionaries” during the late 1960s and early 1970s:

)

)

On a related note on the application of this theory of affect to actual objects: Affect in photographs and other visual art (Goya’s “The Disasters of War,” 9/11 photos, photos of the Vietnam War, Claude Cahun’s self-portraits) – How is affect produced in/by such products, and do they raise it to the level of consciousness?

Siri

Well there’s definitely a lot more going on here than I want to comment on immediately, but I would like to touch on the idea of affect and social obligations. Affect is inherently something embedded for Massumi, and I think this quote (he draws on Deleuze here too but it’s his analysis) kind of gets at that: “What it is saying is that we have to live our immersion in the world, really experience our belonging to this world, which is the same thing as our belonging to each other, and live that so intensely together that there is no room to doubt the reality of it…What it means, I think, is accept the embeddedness, go with it, live it out, and that’s your reality, it’s the only reality you have, and it’s your participation that makes it real” (242). It definitely feels like affect is meant to be something that always takes connectedness to others into account, and that any obligations are just more constraints to be played with, to emphasize the connection between individuals. I don’t know if, beyond that, obligation towards empathy is built in, per se. It’s not clear; Massumi doesn’t really discuss it. I feel like some notions of ethics and obligation do play into the moment of affect, insofar as individuals will only consider as possible what they would also consider ethical – the first response of someone averse to violence wouldn’t be violent, unless the situation was quite extreme, and close friends won’t consider turning on one another unless, again, there’s some impetus that changes the constraints and incentives involved in the space of possibility.

Hi Siri,

Since feeling deeply a situation means being aware of the potentials at hand, maybe empathy in the way Belman and Flanagan conceive of it, that is taking another person’s point of view, is actually closing off a lot of potentials- since empathy requires stopping your own thoughts in order to feel for and with someone else, it necessitates therefore not investing your own time and energy into other potentials. I think Massumi’s idea of affect requires a different understanding of empathy as well. Empathy in Belman and Flanagan assume an autonomous, contained self that needs to be interrupted from a normal flow of life in order to take the perspective of another. Belman and Flanagan’s emotional empathy is more similar I think to Massumi’s idea of capture or abduction: “thought that is still couched in bodily feeling, that is still bound up with unfolding sensation as it goes into action but before it has been able to articulate itself in conscious reflection and guarded language (217)” Empathy, an experience that captures you, “can change you, expand you” in that it breaks your sense of self to include the person you are empathizing with. Sometimes that does indeed make you suffer in a circumstance where you may not suffer, had you kept yourself protected and guarded from someone else’s baggage. BUt that breaking of the self is expansive and Massumi talks about this, too, in pg 239/240.

This also answers your question about how to link freedom back to people and obligations- if you don’t consider yourself as bounded by your own skin and own interests, and are thus able constantly open yourself up and live at the threshold of affecting and being affected, then empathy comes unconsciously. This is probably both a bodily freedom and relaxation (thinking of Vickers’ table of the different body dispositions for therapists, aikkido practitioners, and improvisers) as well as mental one.

To your question about if it is ethically desirable to bring affect more to the level of consciousness-

I remember talking about how ancient bards didn’t have to remember the epic poems they were reciting because the story already existed in their body. In this sense, the bodily affect that comes with a narrative history (the epic poem) is not necessarily conscious, but rather always there and always able to be activated. So I think that affect is not necessarily about being hyperconscious that “I have so many potentials right now!” but rather being in a constant bodily and mental and emotional state that allows for more potentials to always be more present.

To your last question: I think that hate and resentment is the affect that Trump has used, while empathy and love is the affect that we can “capitalize” on, that Massumi urges us to use in an ethico-aesthetic politics, in order to fight division. I was talking to my friend about my ambivalence towards protests (feel like my international background rubs the wrong way against america-centric liberal voices that assume liberal backgrounds and shame nonliberal ones… thats for another conversation), and she was saying how the problem with protests is that they are not creative, and one is very similar to most other ones. I do not know much about the history of protests or protest organization, but a creative protest (my imagination thinks of one that does not shame, that is poetic but also affectively powerful, that is unexpected…) sounds just sounds so expansive and hopeful.

also- what i said in the first part was totally buidling on what @ellapow was saying